PROBLEM QUESTION 1

NORTHERN IRELAND

Background: LAWS601 International Law

Britain constitutes the largest among a group of islands to the northwest of mainland Europe. Britain is divided between three countries: England, Wales and Scotland. A political union has existed between England and Wales since the 13th century, but the Kingdom of Great Britain, incorporating Scotland, did not come together until 1707. Just to the west of Britain lies the smaller island of Ireland. Up until the 19th century this constituted a separate kingdom, but in 1801 the two islands merged to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

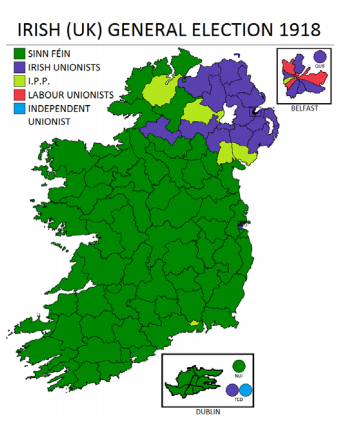

The 19th and early 20th centuries saw a rise in Irish nationalism, expressed as support for Ireland’s separation from Britain. The nationalist uprising of 1916 was quickly suppressed, but in the general

election of 1918 Sinn Féin, the principal party backing the Irish republican cause, enjoyed considerable success. Even so, as shown by Map 1 (below), enthusiasm for independence was not uniform across

Ireland. Support for Ireland’s union with Britain remained strong in the island’s north-eastern corner. This area, which comprises a large part of the historical province of Ulster, corresponds with the part of Ireland that experienced the largest influx of migrants from Britain, particularly during the 17th century. Even today many in Ulster trace their ancestry back to Scotland or England.

In 1920, responding to growing demands for Irish home rule, the UK Parliament voted to divide Ireland into Southern and Northern Ireland. The latter encompassed those parts of Ulster where unionist support was strongest. Meanwhile, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) was waging a guerrilla war in support of Irish secession from the UK. That war culminated in the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, which created the Irish Free State. This provided Ireland with complete independence in its home affairs, as well as practical independence over foreign policy. Even so, the treaty gave the Parliament of Northern Ireland, which had come into existence some six months earlier, the option of keeping that province

within the UK. Northern Ireland’s Parliament exercised that option almost immediately, thus bringing about the partition of Ireland. Following a referendum in the Irish Free State (which had come into

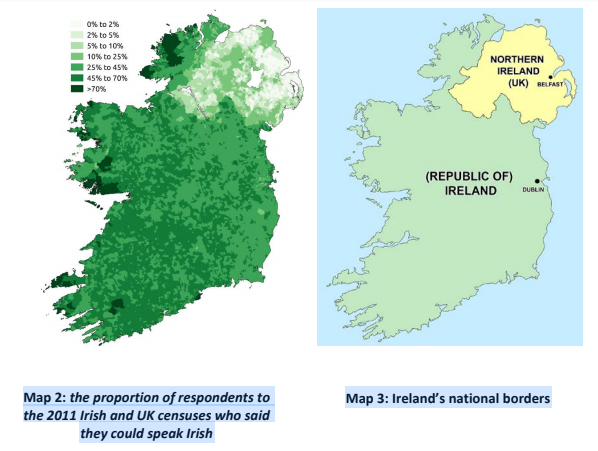

being in 1922), that entity was replaced by the fully independent Republic of Ireland in 1937. Today the Republic continues to govern all of Ireland apart from Northern Ireland, which remains part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (see Map 3).

ORDER This LAWS601 International Law Assignment NOW And Get Instant Discount

Ireland’s cultural and religious divisions are complex. Even so, a crude distinction can be drawn between Northern Ireland and the Republic to the south. Elections and polls repeatedly indicate that the majority within Northern Ireland continue to support union with Britain, while there remains within that region a significant minority in favour of a united and independent Ireland. If taken as a whole, most people who live on the island of Ireland would support a united Ireland. In terms of

religion, Northern Ireland’s unionist population tends to identify as Protestant, while that region’s nationalist minority, along with most of the Republic, tend to define themselves as Roman Catholic.

Map 1 (above): the results of the 1918 general election, showing the concentration of unionist support in the northeast.

Minority languages within Britain and Ireland

English is the day-to-day language of the vast majority of people throughout the UK and the Republic of Ireland. Even so, several traditional, minority languages are spoken in both countries. In terms of

the UK, the most widely used is Welsh, the historical language of Wales. Today around 19% of people in Wales can speak Welsh. In 1993 the UK Parliament passed the Welsh Language Act, which put Welsh on par with English as far as the public sector within Wales is concerned. Then in 2011 the National Assembly for Wales passed the Welsh Language (Wales) Measure, making Welsh an official language in Wales.

In terms of Ireland, the island’s minority languages include Irish and Ulster Scots. The latter is a form of the Scots language, which arrived in Ulster during the 17th century, along with a large contingent of immigrants from Lowland Scotland. Ulster Scots speakers barely exist within the Republic and even in Northern Ireland only around 1% of people profess to speak the language.

Irish, on the other hand, was the vernacular of most of the island of Ireland’s inhabitants until the early 19th century, when it began to give way to English. In recent years the Irish language has enjoyed something of a resurgence, being widely taught in schools in the Republic, as well as some schools in Northern Ireland. Today up to 10% of the island’s population speaks the language regularly outside of the education system. Like those with knowledge of Ulster Scots, almost everyone who can speak Irish can also function in the English language.

ORDER This LAWS601 International Law Assignment NOW And Get Instant Discount

To a considerable extent use of the Irish and Ulster Scots languages reflects Ireland’s religious, cultural and political divides. Ulster Scots is most likely to be spoken by inhabitants of Northern Ireland who identify as Protestant and loyal to the union with Britain (loyalist). Conversely, Irish is least commonly encountered among Northern Ireland’s loyalist population. As shown by Maps 2 and 3 (above), the area where Irish is spoken the least corresponds almost exactly with that part of Ireland that remains within the UK.

The Fact Scenario

It is now March 2022. Having graduated from Macquarie Law School, you are working for a large, international law firm based in Sydney. Your supervisor in the firm, Mairona McTiernan, hails from Belfast. Like many partners in the firm, Mairona has a reputation for pro bono human rights work. She is noted for her expertise in UK law, but not in public international or Australian law, areas she never studied. As a result, she tends to rely on your knowledge in those fields.

As you travel to work today you take the opportunity to catch up on the news. It is three years since the UK left the EU. At first the transition period, negotiated with the EU, meant that change was barely noticeable. But things were different after December 2020, when the transition period came to an end. In January 2021, in order to fulfil its obligations under its new trade deal with the USA, the UK introduced tariffs on certain goods entering from the EU. Then, in the face of mass smuggling from the Republic of Ireland into the North, customs checks were introduced along the Irish border. Almost immediately violence erupted on the streets of Belfast, as angry crowds protested at what they saw as a breach of the Good Friday Agreement. Many now fear that Northern Ireland is sliding towards a return to The Troubles.

Q1 (worth 10 marks)

By leaving the EU, introducing a hard border into Ireland and calling a poll in 2022, thus effectively augmenting and prolonging the partition of Ireland for at least seven more years, to what extent could Ireland, Pakistan or any other country justifiably claim that the UK is in breach of obligations owed under international law in relation to the following:

(a) the Treaty on European Union;

(b) the ICESCR (in terms of the right of peoples to self-determination);

(c) the Good Friday Agreement.

Q2 (worth 8 marks)

If the UK were to denounce, with immediate effect, the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, and if it were to permit schools in Northern Ireland to choose which (if any) minority languages to teach, to what extent could Ireland, Pakistan or any other country justifiably claim

that the UK would be in breach of obligations owed under international law in relation to the following:

(a) the ICCPR;

(b) the ICESCR;

(c) the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages;

(d) the Good Friday Agreement;

(e) the St Andrews Agreement.

Q3 (worth 5 marks)

In addition to the steps outlined in Q2, if the UK were to permit schools in Northern Ireland to prefer speakers of Ulster Scots over other candidates when it comes to hiring teachers, to what extent could Ireland or any other country justifiably claim that the UK would be in breach of obligations owed under international law in relation to the ICESCR?

Your task:

Write an appropriate response to your supervisor, answering her questions and explaining the reasons for your answers. In doing so, note the following:

1. You should write as you would in the real world if you were charged with such a task. However, one artificial aspect of this exercise is that you should include full citations just as you would in any academic writing. The citations should take the form of footnotes that comply with the Australian Guide to Legal Citations (3rd edition).

2. In advising your supervisor you should assume that there have been no relevant changes to UK or public international law subsequent to 27 March 2018 (save for those indicated in the fact scenario).

Criteria for marking the opinion:

Your response should:

1) demonstrate an understanding of the relevant areas of international law covered by Topics 2 to 5 (inclusive) of this unit;

2) demonstrate an ability to conduct your own independent research where needed to supplement the lectures, prescribed readings and provided facts;

3) apply the relevant principles of international law to the fact scenario, asking for relevant additional information only where necessary;

4) provide accurate, appropriate advice;

5) be written in a clear and concise style, observing the grammar and syntax of English. In particular, write in complete, grammatical sentences, not note form;

6) be presented in single spacing;

7) include a statement of the word count (excluding footnotes) at the end.